THE PERFECT MACHINE requires no maintenance, no repairs, and no aftermarket service of any kind. Once it goes out the door, you forget about it. Because thats not possible with any machine more complex than a bench vise, the next best thing is a machine that requires the absolute minimum of changeover effort, maintenance, repairs and service. How do you build such a machine? We asked machine builders and automation suppliers what they do towards that goal, and got some interesting answers. Basically, they say to keep it simple, monitor it, and fix it before it breaks.

Kiss Your Troubles Away

Mechanical devices cause most of the problems in most machines. Traditional motors, gearboxes, line shafts, belts and chains require endless adjustments and maintenance, and are prone to failure after prolonged use. Parts changeovers often are tedious and time consuming for your customers. The better solution would be to look for a way to keep it simple, stupid (KISS).

R. A. Jones & Co. in Covington, Ky., has made packaging machines for 100 years, and theyve kept up with technology all the way. Manufacturers that use carton machines are in an extremely competitive mode, says Darren Elliott, chief engineer at R.A. Jones. They need to run products faster and more efficiently. In 2000, R.A. Jones began implementing what is known in the industry as Generation 3 (Gen3) machines, using Rockwell Automations Kinetix motion control system, servo drives, a digital SERCOS network, and MP-Series motors and actuators.

FIGURE 1: DRIVE, HE SAID

R.A. Jones has been building cartoner packaging machines for 100 years. In its new cartoner machines, the company changed over to servo drives to reduce the number of mechanical components and increase reliability.

What Condition Is Your Condition In?

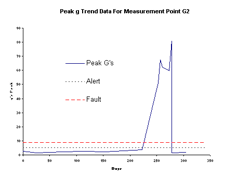

Simplifying the machinery is just one step. Determining when a problem is going to happen is the next step. This calls for condition monitoring and analysis. Essentially, you install condition monitors such as vibration and temperature sensors on the machine, acquire all the data in real time, and compare the data to a baseline signature to determine if a problem is getting severe enough to require maintenance.

Mechanical failures are wonderfully predictable, argues Mike Fahrion, president of B&B Electronics.

The predictive-failure indicators are generally well-known. A motor manufacture can supply a control chart for temperature, vibration, current and other parameters. From there it's simply a matter of instrumenting, data logging and analysis.

GRAPHIC RESULTS

Make Money From Monitoring

Jack Bernard, business development manager, Rockwell Automation Integrated Condition Monitoring, offers a financial reason for machine builders to use condition monitoring. Machine builders benefit by reducing their post-sales support to the end-user, he explains. Specifying a condition monitoring system and condition-based maintenance program, as well as a parts management agreement, phone support contract, and a preventive maintenance contract, allows the machine builder to do what it does best--build machines, not support them. Further, they can avoid or lower the costs of warranty repairs.

Although many condition monitoring systems running today were installed by the end user, this is not something that customers really want to do any more, says Chris DeFilippo, product engineer at National Instruments. Now its a job for the machine builder. And its profitable. In general, end-users do not want to develop their own PM systems because of real or perceived problems associated with high cost or the difficulty of implementation, he says.

Machine builders have the opportunity to build extra value into their products by incorporating condition monitoring into the control systems using programmable automation controllers (PACs). With built-in memory and performance-grade processors, PACs can provide continuous, on-line machine monitoring and diagnostics, while performing complex control. One of the ways machine builders use PM systems to differentiate themselves is by guaranteeing equipment uptime and offering extended warrantees on machines with condition monitoring. Customers benefit from more reliable equipment and are willing to pay a premium for this advantage.

Fahrion agrees that the machine builder can benefit greatly. It could create an entirely new value proposition, he notes. Who better to analyze sensor data than the builder? The technology already is in place so this data could be piped back to a server at the manufacturer. They now could sell a PM scheduling service that would save the end-user money. Warranty claims should drop to near zero.

Warranties could be extended to lifetime when the service contract is purchased, since the machine builder would have complete insight into failure prevention for each installation. The machine builder also would now have access to a phenomenal amount of data about its own equipment. Analyzing that data should allow them to further refine their equipment at a design and manufacturing level. This could drive an entire new level of QA.

Of course, nobody said condition monitoring is easy. It requires expensive sensors, data acquisition equipment, and analysis software. Then, the machine builder has to run baseline tests, so it knows what failure conditions look like in the various systems in the machine.

Computer power and software analysis tools are not expensive, says Fahrion, but the cost of instrumenting the system can be too high. He says wireless is one way to avoid high wiring costs. The perfect solution is for condition sensor data to flow into analysis software via wireless connections. No data cables, no power cables. IEEE 802.15.4 is poised to pull this off.

How Much is Not Expensive?

Many of the contributors to this article suggest that the cost of predictive maintenance for machine builder and/or customer is not prohibitive. Our research estimates that it costs somewhere between $4,000-7,500 to instrument a machine and acquire the data. The cost of the condition monitoring, asset management and maintenance management software needed to analyze the data and make predictions ranges from economical to astronomical. These costs might be coming down rapidly, because some of the big guns in the control industry are stepping into the condition monitoring business. For example, Emerson Process Management now sells a machinery health monitor for motor-pump trains. It includes vibration and temperature sensors, a machine-mounted analyzer, and a network link, all for $5,000-$7,000. This is just might be the beginning of a trend that will shake the condition monitoring industry to its core, and result in falling prices across the board. Competition has a way of doing that. For the moment, a machine builder has to decide: Is it worth adding $5,000-$7,000 to the cost of each machine to obtain all the benefits noted? Should they make condition monitoring available to customers as an extra-cost option? Will it sell? Or can they make the investment back on reduced service and warranty costs?In any case, simplifying the machinery and then using condition monitoring to check for potential faults seems to be the wave of the future for machine builders. Sponsored Recommendations

Leaders relevant to this article: