- How do packaged goods manufacturers approach retrofitting?

- How is industry addressing the shortage of experienced technical employees?

- How much importance should the packaging equipment industry place on the IIoT and the productivity gains that big data promises?

- How will IP67 and IP69K components affect machine-design decisions?

As consumers grow hungrier and hungrier for packaged goods that satisfy their appetites for variety, it is having a profound effect on manufacturers that reaches all the way back to the machine builders that make the packaging equipment used in these production operations. Our panel of experts answer questions on topics ranging from changeover and retrofits to skilled employees, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and moving components out of the cabinet.

With increasing consumer demand for variety, production and packaging companies have seen a narrowing window to bring a concept to reality. How do the quickly changing consumer trends affect the design, form and function of packaging machinery?

Machines must be simple and fast to change over. We have folks looking into automating our changeover of case guides, so that setup is repeatable, as well as fast. Our machines are relatively simple mechanically. Changeover is primarily recipe and a new tool.

Certainly, packaging equipment and machinery are becoming more flexible to meet changing applications, as dictated by rapidly changing buying habits of consumers, and conveyors are no exception.

Figure 1: Sometimes the best way to navigate an obstacle is to go up and over. These types of conveyors are designed with one or two pivot points, allowing the conveyor to be adjusted at different angles. When operational, these conveyors are an effective solution when space is tight, as they act as a bridge to divert product flow up and over an obstacle, or conversely down and under.

(Source: Dorner Manufacturing)

When you talk design, form and function of a conveyor, what you’re really talking about is how adaptable is it with other processes and machinery within a packaging line. In the olden days, conveyors for the most part moved things from Point A to Point B, and that was pretty much it. Today, conveyors are engineered to do so much more, and part of our challenge is educating our customers—design engineers, product managers, plant managers, integrators—about all the capabilities conveyors bring to the table. Conveyors have become integral components in packaging lines, and in many cases, contribute to making a line operate much more efficiently.

Having a good understanding of the capabilities of conveyors can really assist a design engineer or integrator to build a system that ultimately helps the customer to solve a material-handling challenge. I think our Z-Frame or LPZ Series conveyors are a good example of this added flexibility of conveyors (Figure 1). These types of conveyors are designed with one or two pivot points, allowing them to be adjusted at different angles. Z-Frame conveyors are an effective solution when space is tight, as they act as a bridge to divert product flow up and over an obstacle, or conversely down and under.

Adding to conveyor capabilities are accessories. For example, manufacturers can mount shaft encoders to the conveyor’s drive shaft to sense rotations, count pulley revolutions and control the belt in feeding or indexing applications. Diverters and gates manage the product’s continuous flow on the conveyor. Controlled by proximity switches, photo eyes or counters, they guide and change product direction to single or multiple locations. In addition, diverters and gates meter flow to specific areas or separate products based on attributes.

Depending on the product and required stroke length, pushers mount overhead or on the conveyor’s side to remove items flowing perpendicularly from the conveyor. Servo drives accurately stop the conveyor to provide precise part location. They help to control acceleration and deceleration and assist in assembly operations.

Packaging machinery must be more flexible to accommodate consumer demands. This requires software-based automation of as many functions as possible including real-time control, operator interface and motion control. PLCs should be used instead of hardwired relay logic; touch panels should be used instead of push buttons, lights and meters; and servo systems should be used instead of electromechanical motion control. Adding I/O to the PLC should be easy, either by adding more I/O modules to a rack or by connecting more I/O to CPU via a digital network.

Jim Hulman | process, packaging, printing, converting—business development manager, Bosch Rexroth

Today, machine design starts at the packaging concept stage. Bosch Rexroth has teamed up with Dassault, parent of Solidworks, to combine Dassault’s virtual mechanical machine with Bosch Rexroth’s actual control program. Rather than building a mechanical machine and then adding controls and programming, the new process provides simultaneous mechanical, electrical and controls engineering. This creates a digital twin of the machine and control system. The digital twin runs virtual products, testing out product manufacturing feasibility and machine design. In the case of mechanical interferences or product flow issues, electronic bits crash, not physical components. Redesign and adjustment are made electronically before even one part is made. This greatly reduces the design cycle and shortens machine debug time.

Companies that are prepared and know in advance the areas of a machine that can be tailored to customer needs can set themselves apart by quickly adjusting to consumer trends. A way to get ahead is with a modular and configurable machine. With a modular approach, you can efficiently answer to customers’ requests by configuring a machine. This configuration will select the relevant module and the variants, and it will assemble them. Additionally, you can specify modules depending on your company strategy. This will help the continuous improvement of your machine, allowing incremental innovation. For example, you can gather in a module called “style” all the components that will be impacted by a change on the design. If a customer asks for a specific shape of your machine, the module “platform” will remain unchanged, but the module “style” will be modified, and all other modules will not be affected.

The reduction of development cycle time led manufacturers to modify the machine architectures in order to make them more modular by integrating more software and electrical components. But it increases the complexity of the machines and makes their development more difficult. This is why it becomes critical for the manufacturers to change the way of developing modular machines by adopting a model-based system engineering (MBSE) method that reduces complexity for all stakeholders and increases the productivity and communication of a project thanks to a common language.

John Kowal | director, business development, B&R Industrial Automation, Control System Integrators Association (CSIA) member

I spent 11 years focused exclusively on the packaging machinery industry, and there is an emerging trend that I'm calling, “The Adaptive Machine.” Ten and 15 years ago, we talked about Gen 3 or third generation—a term SIG coined for the 1999 interpack fair—distinguished by mechatronic design to take full advantage of servos.

Gen 3 gave us things like continuous motion, no homing at restart, fast and sometimes automated changeovers. Since then, concepts such as modularity, interactive HMI, embedded robotics, vision, automated changeover and networked safety have incrementally increased performance.

The next generation of machine, Gen 4, will allow the machine to adapt to the packaging requirement, instead of the packaging process dictating machine design. The adaptive machine will give us motions that are independently controlled for batch-of-one manufacturing, no need to restart because of safe motion and robotics, and changeovers replaced by inline customization. In essence, the machine needs to adapt to the products on the fly.

Track technology will be at the core of the new machinery, providing independently controlled movement, processing and packaging of each SKU. Instead of rainbow packing by hand at distribution centers (DCs), it will be inline with manufacturing. Instead of huge e-commerce DCs, batch-size-one will become economical and will be built and shipped to order from the factory.

Figure 2: Use of position or feedback devices and RFID technologies can error-proof and ensure the changes are in line with the recipe.

(Source: Balluff)

Shishir Rege | marketing manager, networks and safety, BalluffWith the new trends in consumer taste and product interests, to remain competitive in the global market, packaging companies are required to update their machines to satisfy today's demands. We are changing from mass production to mass customization or small batch production. This requires machines and systems capable of quick changeovers that reduce downtime required to change machines for the next batch of products or packaging. Adding to this mix is ever-changing packaging to satisfy constantly changing consumer product appeal. It is almost imperative that the machine changes are almost instantaneous.

Figure 3: Technologies such as IO-Link can be of tremendous help in the areas of error-proofing and visualization, as it offers remote parameterization and smart communication over the standard sensor cables.

(Source: Balluff)

In order to achieve just-in-time format changes in the machine or to the machine requires three critical processes: automated format change; error proofing the format change process; and lastly visualization or alarm for the problem areas that can be quickly tended to.

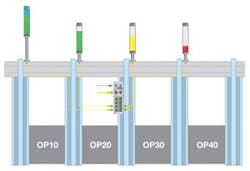

For automated format changes, machines may have magazines of tools that can be moved or replaced based on the production needs. Use of position or feedback devices and RFID technologies can error-proof and ensure the changes are in line with the recipe (Figure 2). Technologies such as IO-Link can be of tremendous help in the areas of error-proofing and visualization, as it offers remote parameterization and smart communication over the standard sensor cables (Figure 3). The remote parameterization feature enables controllers to send the new calibration data to the sensor so that these sensors and measurement devices are ready for the next measurement. A good example for error-proofing and visualization would be a linear transducer reading the position of the tool in the machine; a tower light indication device could show by changing colors whether the new position is within the required tolerance or not (Figure 4). The visual indication helps the maintenance person to quickly tend to the areas that may not have adjusted properly to the new format. Another example would be the RFID system reads the tag on the new tool and informs the controller if the expected tool is present in the system; again through visual indication the maintenance staff can be assured or alerted of the situation.

ALSO READ: The future of packaging machinery design

Figure 4: A good example for error-proofing and visualization would be a linear transducer reading the position of the tool in the machine; a tower light indication device could show by changing colors whether the new position is within the required tolerance or not.

(Source: Balluff)

Mike Bacidore is the editor in chief for Control Design magazine. He is an award-winning columnist, earning a Gold Regional Award and a Silver National Award from the American Society of Business Publication Editors. Email him at [email protected].