This is Part III of a three-part series on laser processing with modular control. Read Part I and Part II.

Laser material processing is now a significant aspect of industrial manufacturing, used for tasks ranging from heating for hardening, melting for welding and cladding and the removal of material by drilling and cutting. Many of the technologies would benefit from a system that could synchronize laser pulse control with motion.

For example, high-intensity femtosecond laser processing, which is becoming more common as more industry-proven commercial lasers become available, is considered a cold process because the material being processed does not heat up during the interaction. This type of processing includes texturing of surfaces to decrease reflectivity, provide hydrophobic surfaces or create chemically reactive surfaces. It is of particular interest in the automotive industry, where the push for improved efficiency is driving the reduction of friction of moving components, to lessen the use of lubricant consumables and improve durability. Another useful property of the cold ablation of high-intensity lasers is the ability to drill clean, small, deep holes in materials without damaging the surrounding material. This technology is now commonly used in the medical industry for fabricating vascular stents, and it has been widely adopted for holes with diameters of microns and a large depth-to-diameter ratio.

Other applications include the dicing of glass that allows the processing of the back of a surface without damaging the front. This application is simply not possible using conventional mechanical diamond-blade dicing techniques.

Micromachining and welding are commonly carried out by nanosecond fiber lasers. Although the fiber laser has longer pulse duration than femtosecond lasers, it can be used with careful control of pulses and processing parameters. In this type of laser processing, the energy is eventually converted into heat that dissipates out of the laser spot, beyond the duration of the laser pulse. Essentially fiber lasers keep costs lower, so, if the process is controlled and the results are suitable for the application, they make a lot of sense. In all of these applications, controlling the pulse duration, frequency and placement is key to changing the laser process capabilities, quality and intermolecular interactions.

Basic modes of operation

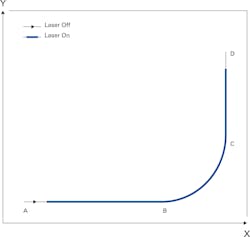

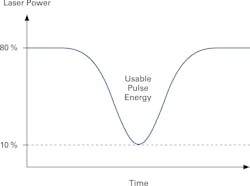

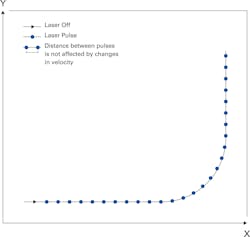

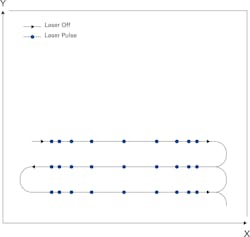

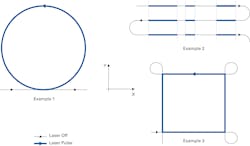

The simplest method of laser control is to define the switch-on and switch-off positions. The laser power control is set by the laser itself, or an additional analog input is used for power related to speed (Figures 1 and 2). The next method to consider is distance-based pulse control, which is when the laser expects to see a trigger at a fixed distance along the path. The user defines the switch-on and switch-off positions, as before, but the firing signal is not continuously on. The controller may use this pulse to create a single shot from the laser or a combination of pulses for a particular laser processing recipe.

User-specified output pulse generation

The combination of high resolution, multiple axes and high speed within one system can be problematic for a user to calculate the distance along the outputting vector path. Fortunately, laser firing modules like the laser control interface (LCI) can calculate the vector path for you. This makes it simple to define a fixed distance along the path, even when the path may be physically in one direction or a combination of multiple axes.

Firing at defined positions along a path—array-based or random firing

Rather than telling the system to fire at fixed discrete positions, it is also possible to define an array of positions where firing occurs. This can be used when an event may trigger a single shot or an alternative processing regime, for example, due to a material or process change—cutting vs. welding (Figure 5).

Isolating an area of interest—windowing

Some users may simply need to tell a laser where to turn itself on or off. The laser power may be controlled, for example, by an analog input, typically a 0-10 V signal. Alternatively, laser power can be controlled by a combination of modes, for example, fixed-distance pulsing or PWM. Windowing can be overlaid with these methods to simplify the laser processing areas. This typically uses an array method to define the start and end of the window (Figures 6 and 7).

PWM mode

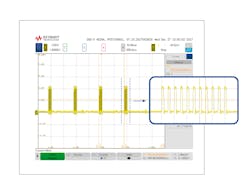

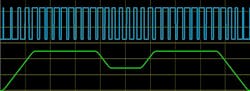

This method is very common in electronics, directly controlling laser power by using PWM to adjust the duty cycle. Hybrid modes are also available that combine PWM with pulsing at user-defined intervals, allowing nonlinear or varying firing events. In addition, zones of operation can be created, giving even tighter control over where firing or modulation takes place (Figure 8).

Summary

Fast and ultrashort laser sources open up opportunities for system integrators to incorporate these technologies into new applications. New tools offer the ability to process smaller features in a different way that was not previously possible.

However, for processes that require motion in the form of linear, rotary and nonlinear kinematics, it is essential that the laser firing is synchronized accurately with the motion path positioning. Electronics that allow this have been available in specialized motion controllers for some time, but industry is moving toward networks such as EtherCAT that make it simpler to add or link laser pulsing hardware. The significant advantages for the system integrators and builders of electrical cabinets brought by this level of connectivity allow them to choose the appropriate motion amplifiers and controls for the motion and the right interfacing for the laser.

Dr. Cliff Jolliffe is head of the automation market segment at Physik Instrumente (PI). Contact him at [email protected].